Introduction

When a company decides to go public, attention usually gravitates towards valuation, timing, and market conditions. Yet, one of the most fundamental and often under-appreciated decisions in an IPO is this-

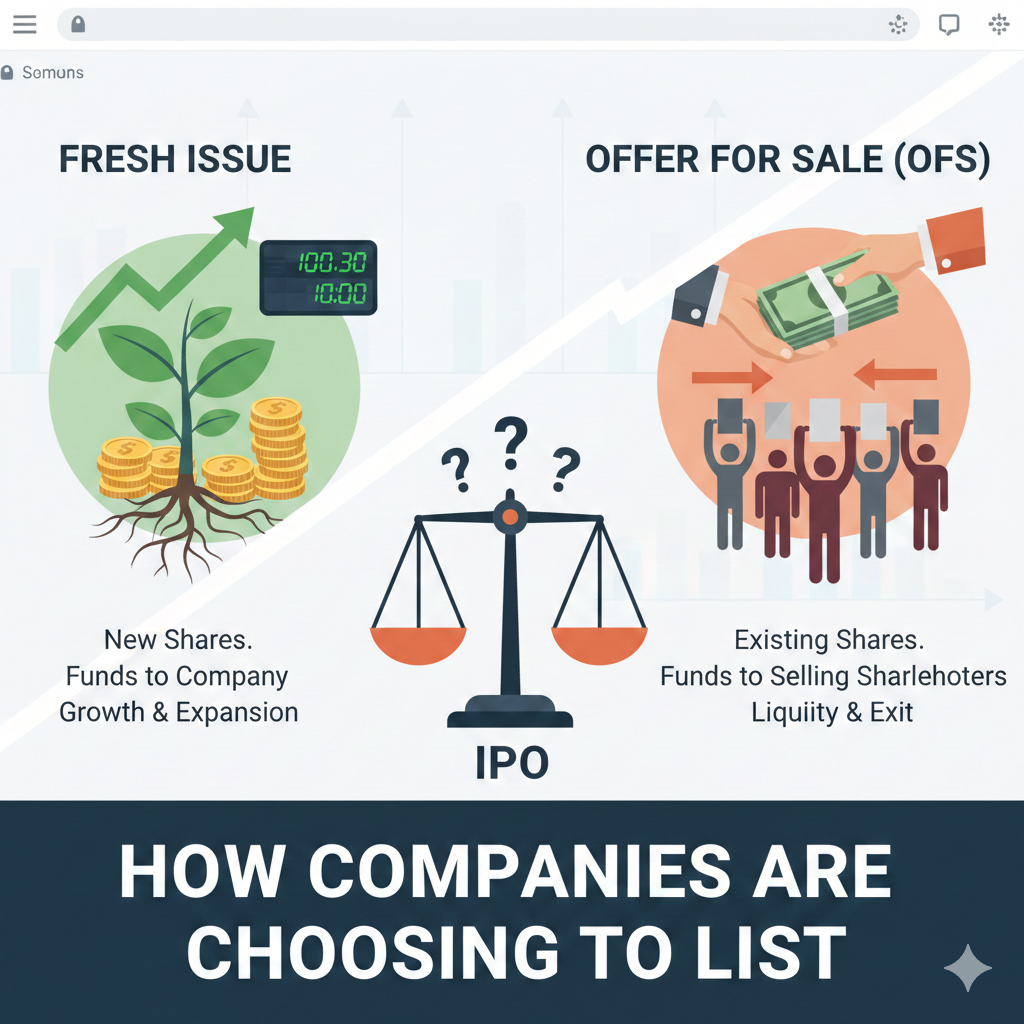

Should the issue be a Fresh Issue, an Offer for Sale (OFS), or a combination of both?

This choice is not merely technical. It influences how investors perceive the IPO, how regulators scrutinise disclosures, and how the company’s post-listing journey unfolds. For promoters-especially those approaching the capital markets for the first time-understanding this distinction is essential.

Understanding the two routes: same IPO, different outcomes

An IPO can broadly be structured in two ways.

1. Fresh Issue:

A Fresh Issue involves the company issuing new equity shares to the public. The proceeds from the IPO flow into the company, increasing its paid-up share capital. This route is typically associated with growth viz. funding expansion plans, repaying borrowings, meeting regulatory capital requirements, or strengthening the balance sheet.

2. Offer for Sale:

An Offer for Sale, on the other hand, involves existing shareholders selling their shares to the public. No new shares are created. The company does not receive any funds; instead, the proceeds go directly to the selling shareholders viz. usually promoters, private equity funds, or early investors.

While both structures result in listing, the economic substance of each is quite different.

Who needs the money decides mode of IPO

The most effective way to think about this decision is to ask a simple but honest question:

Does the business need capital, or do the shareholders need liquidity?

If the company is entering a phase where it requires funds for growth, capacity expansion, acquisitions, or debt reduction, a Fresh Issue becomes a natural choice. Investors generally view such IPOs positively, provided the use of funds is clearly articulated and commercially sound. Dilution of promoter shareholding is seen as acceptable when it is tied to future value creation.

However, empirical IPO data tells a more nuanced story.

Between December 2024 and January 2026, covering 103 Mainboard IPOs and 294 SME IPOs, the following pattern emerges:

| Issue Structure | Mainboard IPOs | SME IPOs |

| Only Fresh Issue | 0 | 4 |

| Only Offer for Sale (OFS) | 16 | 20 |

| Fresh Issue + OFS | 87 | 270 |

| Total IPOs | 103 | 294 |

Table 1: Details of IPOs between December 202 to January 2026

This means that over 90% of IPOs across both segments adopted a combined structure, and pure Fresh Issue IPOs were virtually absent, especially on the Mainboard.

Conversely, if the business is already generating sufficient internal cash flows and does not require external capital, an OFS may be appropriate. This is particularly common where early investors are nearing exit timelines or where promoters seek partial monetisation after years of value building.

However, perception plays a critical role. An IPO that is largely or entirely an OFS can sometimes be viewed as an “exit IPO” unless the company’s fundamentals and growth prospects are strong enough to counter that narrative.

Growth story versus exit optics

Every IPO, intentionally or otherwise, tells a story.

A Fresh Issue-heavy IPO signals that the company is focused on scaling operations and investing in the future. An OFS-heavy IPO signals that existing shareholders are unlocking value. Neither is inherently good or bad, but each sends a different message to the market.

This is why many well-received IPOs adopt a balanced structure, combining a Fresh Issue with a partial OFS. Such a structure allows the company to raise growth capital while also providing liquidity to early risk-takers, without appearing promoter-driven or speculative.

Regulatory considerations quietly shaping the structure

Another factor that often drives OFS decisions is compliance with minimum public shareholding norms. Promoter holdings in unlisted companies are frequently well above post-listing thresholds. In such cases, an OFS is not a matter of choice but necessity, aimed at achieving regulatory compliance rather than facilitating an exit.

Fresh Issues, meanwhile, attract closer regulatory scrutiny. Under the SEBI ICDR Regulations, companies must provide detailed disclosures on the objects of the issue, timelines for utilisation, and in certain cases, ongoing monitoring of fund usage. While this increases compliance burden, it also enhances transparency and investor confidence.

Accountability after listing

Fresh Issue proceeds come with an implicit promise. Post-listing, analysts and investors closely track whether the company deploys funds in line with stated objectives. Deviations, delays, or vague utilisation can impact credibility and stock performance.

OFS structures do not carry this burden, as the company is not receiving funds. This makes OFS administratively simpler but also means the IPO must stand purely on the strength of the existing business.

How promoters should think before finalising the structure

Before locking in the IPO structure, promoters should internally evaluate:

- Whether raising capital today will meaningfully accelerate long-term value creation

- Whether promoter dilution is being undertaken for growth or convenience

- How the IPO structure will be perceived by a first-time public investor

- Whether the company’s story remains compelling even without fresh capital

These questions often matter more than pricing mechanics or short-term market sentiment.

Closing thoughts

There is no standard formula for choosing between a Fresh Issue and an Offer for Sale. The right structure depends on the company’s financial position, growth plans, shareholder objectives, and regulatory landscape.

At its core, the decision is about alignment between the company’s needs, promoter intentions, and investor expectations. IPOs that get this alignment right tend to inspire confidence long after the listing day excitement fades.

For promoters, the objective should not merely be to list, but to list credibly, sustainably, and with a structure that supports the company’s next chapter.

This article is published on the Taxmann link share below.